- Home

- Patsy Whyte

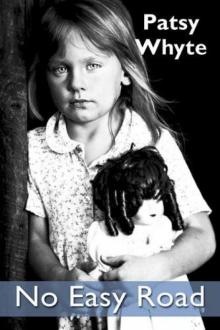

No Easy Road Page 2

No Easy Road Read online

Page 2

"Patricia!", said a tall slim dark haired woman. "Do you know who this is?"

I looked at the boy and he glowered back at me. There was no trace of a smile anywhere on his face. Even I could tell he didn’t want to be here. It was very plain.

"No", I replied, in a disinterested matter of fact voice.

"This is your brother Billy."

I suppose the woman wondered why there was so little reaction from me. Maybe she was disappointed. Her words meant nothing simply because I didn’t know what a brother was. I was more interested in peddling my bike. Perhaps my brother Billy watched me as I took off at break neck speed towards the orchard, which marked the limits of the garden. When I glanced back for a second, he and the woman were gone and that was that. I never thought any more about it. A couple of months later I would meet him again, when I was transferred to Rose Hill Children’s Home.

* * *

I was too old to stay at Airyhall but much too young to know where I was going. All I knew was it was now time to leave my little room. This was my first time going outside in the dark. I felt quite excited. A tall lady with black hair and wearing a tightly fitting Tweed coat introduced herself as Mrs Robertson. She led me to the black car parked all by itself in the driveway. I noticed the loud crunching sound made by the gravel under my feet. Everything sounded so different in the dark. I felt cold. After placing a small cardboard suitcase in the boot, Mrs Robertson opened the front passenger door. I recognised the familiar smell of polish as soon as I climbed in and made myself comfortable on the leather seat.

The night was wild and windy. We drove through the darkness of the countryside without saying a single a word. There was nothing much to see either, but I felt warm and comfortable and sleepy listening to the hum of the engine rising and falling. The light of the speedometer on the dashboard kept drawing my attention. It looked like a clock and I watched fascinated as the large needle in the centre moved round and back, round and back, over and over again. It didn't do much else, so after a while, I became bored looking at it.

The car headlamps pierced the inky blackness ahead and transformed the tall trees on either side of the road into pointing spindly fingers and frightening ghastly faces. Suddenly, I felt a slight bump underneath the car. I lurched forward sharply. Mrs Robertson cried out. My head slammed into the dashboard. Pain. Tears. Confusion. I screamed out in the darkness. The car came to an abrupt stop.

"You're all right, you're OK", shouted Mrs Robertson, repeating the words several times until I finally understood them. I was safe.

Her hand pulled my head backwards and fingers pinched my nose to stem the flow of blood and calming words brought further reassurance.

"Hold your nose", she said after a minute or so had passed. "Pinch it like this."

She pinched her own nose to demonstrate the action so I would understand.

"It will stop", she said in a firm but gentle voice.

I held my nose tightly between my fingers. Mrs Robertson got out of the car to check for any damage. When she got back in again, she handed me a handkerchief to cover my nose. The bleeding had almost stopped. She turned the car around and we drove back to Airyhall.

I was quickly taken out the car and up the large winding staircase to my old room and put straight to bed. I left Mrs Robertson standing in the hall entrance way trying hard to explain what happened. I fell asleep almost immediately but awoke the next morning with a splitting headache. The pain was excruciating. I screamed and cried out until a doctor arrived.

The doctor was young and had a gentle soothing voice and a friendly smile which instantly put me at ease. The pain started to go. He examined me and concluded there was little to worry about. I was probably still suffering a little bit from the shock of the accident and the stress of the move, nothing more.

Then he put a hand in his pocket and produced a shiny new penny and told me to watch carefully. The penny danced across his fingers and disappeared and reappeared again. I was fascinated and laughed aloud. My eyes followed the penny's every movement. By the time the doctor left, the throbbing pain in my head had almost gone and I was now the proud owner of the magic penny. But, try as I might, I couldn’t make the penny dance or disappear across my fingers. Eventually, I lost interest and fell asleep. When I woke up, the magic penny was nowhere to be seen.

Within a couple of days, I was as bright as a button and fully recovered from the ordeal. Mrs Robertson returned soon after and we resumed the interrupted journey to Rose Hill Children's Home. This time, we set off in the afternoon and arrived there without a hitch.

I always thought the name Rose Hill should conjure up picture perfect images of lazy summer afternoons, of beautiful gardens and green lawns, of children laughing without a care in the world. But it never did for me. Instead, it meant grey steel gates and railings with spikes on top. They were always cold to the touch and unyielding, never shrinking in size. Their only purpose was to keep me in and the world out.

Rose Hill was a place empty of love or words of kindness, where potential was wilfully neglected, stifled or just ignored. I grew up believing I was stupid because I was told I was, every day, for years on end. What hopes and dreams and aspirations I ever had, which might have blossomed with a few simple words of support and encouragement and kindness, were dashed by constant insults and words of contempt.

It was a home filled with children whose eyes never laughed. Tragedy touched each and every one of them. Most lost their mothers. Some even saw their mums commit suicide. In this place of sanctuary, where there were no cuddles or soothing words of comfort to be found, every child was simply left to get on with life and tragedy and sadness as best they could. In all my years growing up there, I never heard any child talk about ever having a mother.

Rose Hill was a home with two faces. One face was harsh, cold and indifferent, often hidden and secretive. The other was a shell, a sham, a pretense, which only charitable visitors saw served up with tea and fairy cakes. These regular occasions were stage managed, choreographed, designed to show off a happy, caring, wholesome family environment. Well practiced party songs were always sung at just the right moment to wring out every last ounce of sympathy. Including Nobody’s Child was certain not only to tug at the heart strings but also to loosen the purse strings. Yet these occasions also provided the only opportunity for children starved of attention and affection to be noticed and praised.

As far as I was concerned, Rose Hill meant bitterness, not idyllic images. For many years, long after I walked out through its gates for the very last time, I suffered the same nightmare. Night after night, I screamed and pleaded to be let out. My hands gripped tightly on the iron railings. I shook them as hard as I could. They wouldn't budge. No one heard me. Nobody came. I couldn't escape. Usually I wakened up at this point, always in a cold sweat, my heart racing until I regained my senses and realised it was just my nightmare again.

* * *

My first hour in the home set the tone for all my years there. One minute I was an infant and the next a child. Care was rigid. There was no gentle transition from one to the other. Within minutes of arriving, I would learn the first of many lessons from my new house mother. She ran the home with a set of unwritten rules in her head. To know what they were meant having to break them, unless you were a mind reader. I wasn’t, so I took the punishments and learned quickly. It was the same for most of the children at Rose Hill.

Mrs Robertson and my house mother were too busy chatting to notice me wandering away from their side. Boredom and curiosity had set in. The heavy green door a few steps along the hallway was too much of a temptation. I wanted to know what lay behind it. So I tiptoed over and gently turned the bright brass door handle. The door opened easily and I peeked in.

Shadows flickered across chocolate brown painted walls. I couldn't see very far inside but I knew it was a kitchen and it was empty. There was nobody about. I stepped through into the creepy atmosphere only to turn around sharply as the door

closed behind me with a long drawn out groan. The kitchen felt warm.

My curiosity of a few seconds ago was all but gone now, replaced by a slight nervousness. I moved quickly towards the centre of the kitchen, past a large square wooden table almost white with years of scrubbing. Tucked neatly underneath were four high backed chairs. They were much taller than me. My gaze searched out the shadows and dark corners and settled on the flames dancing and leaping behind the small window of an old Victorian black leaded stove tucked into an alcove a few feet away. A large black kettle was whistling quietly on the hotplate. Steam gently played across the alcove's cracked blue and white patterned tiles.

Gradually, I began to see more and more of the kitchen as my eyes grew accustomed to the half darkness. To the left, a wooden door with large decorated panels stood slightly ajar. To the right of the alcove was the tall narrow frame of a wooden window, the lower half partially hidden by the solid outline of a white stone sink.

The door had no handle, which was why it was left open. I reached out and curled my small fingers around its sharp jagged edges and pulled hard. The door barely moved. The bottom edge just scraped along the stone floor and stopped. But my will was strong. I was determined to prise it open. With a final tug, the door suddenly lurched towards me to reveal the inside of a large pantry.

I was pleased as punch. High up on wooden shelves stood rows of jelly jam jars filled with home made raspberry jam. The jam looked delicious, tempting, but the jars were well out of reach. I desperately wanted a taste. The more I looked at the jam the hungrier I felt. I hadn't eaten anything since leaving Airyhall.

I pondered for a moment, wondering how I could get up to the shelves. Then I remembered the chairs underneath the table. I began dragging the nearest one towards the pantry door. The chair was very heavy and awkward to move. I realised it was going to be a difficult task. But I was starving and the raspberry jam beckoned.

It took some time to finally manoeuvre the chair into the correct position. I clambered up and balanced on tiptoes and stretched out my fingers as far as they could go. It was enough. My fingers touched smooth cold glass. Very gently, I eased the jar over towards me and down it came. It was now firmly in my grasp. The jar was mine.

Without wasting a further precious second, I ripped off the paper lid and scooped out handfuls of sticky jam straight into my mouth. It tasted delicious. I was too busy enjoying myself to care about the state I was in. I was covered in jam. It was all over my face and hands and in my hair and on my jumper. I was a mess. The kitchen door suddenly flew open.

"You little thief. What do you think you're doing!"

I jumped with fright and almost tumbled from the chair. My hand was still in the jar as I bowed my head in shame. I was guilty, caught red handed. Instinctively, I knew the sharp angry voice belonged to my new house mother. I turned to face the monster. Her eyes glared at me and pinned me to the spot. I couldn't move. I was terrified. She grabbed me by the ears and hauled me off the chair. I cried out in pain.

"I'll teach you to never take anything out of that cupboard again", she shrieked.

My feet barely touched the floor. She dragged me over to the sink and turned on the tap. The water felt ice cold. I howled and screamed and squirmed while she scrubbed and scraped and tugged at my face until satisfied I had learned my lesson. I would never forget it. Many years passed before I set foot in the pantry again.

* * *

There were eighteen children sitting either side of a long wooden table. I was the youngest. I was also the smallest. We all sat in complete silence. Two large white bowls stood in the centre of the table. One was filled with hot porridge and the other with milk. They were placed there by the house mother just before she led us single file into the dining room.

I was a little apprehensive, not knowing quite what to expect or how to behave. So I copied everyone else and sat as still as a statue, my arms at my side. The other children kept throwing me quick glances out the corner of their eyes. I tried hard not to look at them. But I was a stranger in their midst, an object of curiosity.

Steam rose slowly from the old cracked porridge bowl in a lazy curling motion. I followed it upwards until I found myself gazing at a picture of Jesus hanging on the wall facing me. He was holding hands with lots of children from all over the world. There were red and yellow children, brown and black children as well as white. They all crowded round Him in a big circle. Some of the small children gazed into His eyes. Their faces beamed with love and He smiled gently back at them.

The loud click of the dining room door closing brought me back down to earth. The house mother's looming presence, demanding perfect discipline, no longer hovered over us. Where a moment ago there was order, now only chaos reigned. A cacophony of cries and screams replaced the silence. Little angels changed into snarling animals. Fingers nipped and nails scratched. Elbows dug deep into unprotected sides in a desperate bid to grab the lion's share of the porridge.

Other children fought hard for the milk bowl which disappeared under a mass of greedy grasping hands. I couldn't take my eyes off the girl with the red ginger hair. She shoved and pushed the hardest and screamed the loudest until the heavy bowl lay cradled protectively in her arms. No one could get it now. She let out a wild howl of triumph.

The girl slowly lifted the bowl to her lips and gathered a mouthful of milk in the back of her throat and gargled loudly. All eyes turned to watch in awe. The dining room fell silent. Through gaps in her front teeth, two perfectly formed squirts of milk arced through the air, almost in slow motion. They landed with a plop and a splat, bang in the centre of the bowl. A cheer went up. Her fist punched the air in delight. I felt disgusted. I couldn't face eating any breakfast now.

Small blue plastic breakfast bowls dived in to scoop out the contents of the porridge bowl. Within moments, it was almost empty. I looked up and down the table which now resembled the aftermath of a battle. Blobs of porridge and milk shaped like little islands lay splattered all over its surface. The noise got louder and louder as children shouted and screamed at each other and argued to the point of blows over nothing in particular.

The dining room door opened with a sharp click and the noise stopped abruptly. Children sat bolt upright in their chairs once more as if some switch had been suddenly pressed somewhere. You could have heard a pin drop. Jesus smiled. We all filed out of the dining room as quietly as we entered it, led by the house mother who never said a word. My first breakfast at Rose Hill was over. Within a day or so, hunger overcame my disgust. Weeks later, someone happened to mention the girl with the red ginger hair was my sister, Mary Anne.

Chapter Three

It was autumn and the leaves on the trees outside the home were turning from green to deep red and gold. If it wasn't raining, I was sent outside to play in the playground for hours on end, until the rest of the children returned home from school. The days felt long and they were getting colder.

By now, I was used to the morning routine, the 7 o'clock rise for breakfast, the blue plastic bowl sitting on the table, the piece of cold toast lying on a small white plate at the side, the lumpy porridge. It never varied. I quickly learned just how valuable the slice of toast was.

Toast was currency. You could swap it for a toy. Or it could be used to stop someone reporting you to the house mother. Such bargains were struck in whispers and sign language. If you were fortunate enough to find a thick heely on your plate instead of the usual thin slice of buttered toast, your bargaining power increased many times over. The heely, the end slice of a loaf of bread, was prized by every kid. But it was the luck of the draw whose plate it landed on.

The smell of urine was overpowering. It always came from the same dozen beds. Every morning, without fail, they were soaking wet. The stench filled the bedrooms and the hallway and drifted down the stairs to the dining room. It clung to the school uniforms of the children sitting around the breakfast table. But no one mentioned the smell. It was part of the routine, just like

the lumpy porridge.

After breakfast, the children piled through to the cloakroom to put on the shiny shoes they spent hours cleaning and polishing the night before. Coats were pulled off pegs and quickly donned and then it was single file past the staff member standing at the back door. After a quick comb of the head, each child was hustled out the door and on their way to school.

No Easy Road

No Easy Road