- Home

- Patsy Whyte

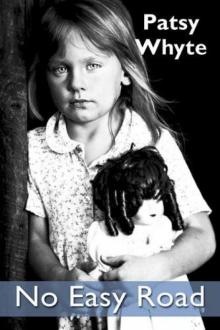

No Easy Road

No Easy Road Read online

No Easy Road

Published by Kailyard Publishing

Copyright 2009 Patsy Whyte

Dedication

For Mum and Dad, James, Georgina, Mary Anne, Lottie, John, Billy, Michael, Andy and Alec. Their road was as difficult as my own.

This book is also dedicated to my partner John, and to Jacqueline, Ian, Kimberley, Samantha and Lucinda, my lovely children.

Chapter One

I was only four when I had my first vision. It wasn't a dream. I was wide awake at the time. It happened in the small dingy cloakroom of a children's home in Aberdeen. A short while before, the cloakroom had been crammed full of noisy kids putting on coats and jackets prior to leaving for school. Now it was quiet. The long line of hooks to hang up the coats and jackets was empty. There was only one little red coat, my coat, left hanging on its own.

It was still early morning. I listened to the sharp clatter of breakfast plates being gathered up in the dining room ready for washing in the old stone sink in the kitchen next door. Outside, the rain poured down. It was a miserable day but I longed to go out and play in the large playground where the hamster lived.

The hamster lived down a drain but so far I’d never seen him. The big boys told me he was there and I believed them. Every day, I poked a stick down the drain and scraped the muck at the bottom looking for him. But he never appeared and my brown woollen jumper and tartan trousers were caked in mud and dirt. I must have looked a sight, judging by the expression of horror on Edith's face. She worked at the home and always called me in when it was time for lunch. First, she had to clean me up, which she hated doing.

The morning dragged on and I became more and more restless sitting on the only chair in the cloakroom, swinging my legs backwards and forwards. I jumped off to look out through the long narrow cloakroom windows. Nothing had changed except the raindrops, which were bigger, hitting off the panes of glass even harder than before.

I peered through the sheets of rain and out across the playground to the high red brick wall at the back of the home. Suddenly, the wall crumbled away before my eyes. I was no longer in the gloomy cloakroom with its cracked and flaking paint but on an empty beach, running bare foot on wet sand at the water’s edge.

A cooling, gentle breeze played across my face and a feeling of pure joy rose within me. I heard the soothing sound of waves lapping at my side and the cry of gulls as they soared high into the clear blue sky above me. Nothing can touch me, I thought, as I ran and ran and ran.

Then my eyes focussed for a moment on a small white cottage barely a speck in the distance. In the next instant, it was there, right in front of me, homely and inviting. The front door was open slightly, leading into a warm and cheerful hallway with white wallpaper covered in small red roses.

I knew there was someone waiting inside for me but as I stepped through the doorway everything changed. The red brick wall formed again and I was back in the cloakroom looking out the window at the pouring rain.

The vision, which I still remember clearly to this day, left a profound impression on me. The beach was everything I longed for, the space and freedom I didn’t have living with 18 other children at the home. What was it about the wallpaper which so caught my attention? It might have been the sheer living beauty of the roses. And who was waiting for me? I still don’t know, but I am certain there really was somebody in the cottage.

I never told anyone about my vision. It was a magical moment meant just for me and it didn’t matter whether I understood it or not. I just accepted it, the way a young child does.

* * *

It took me over 40 years to reach this moment in time. Shortly, I would learn a little about the earliest years of my life and perhaps even discover the reason why I was taken into care. I felt nervous, even a little scared. The two men sitting down with me were social workers, strangers, who I only talked to briefly on the telephone. A new law was in force and now I could look at the file which the authorities kept on me while I was in care. That was why I was here, in a modern and spacious council office five floors up in the middle of Glenrothes. The office had large gleaming windows looking out towards Falkland Hill in the distance and the enormous swathe of Fife lying in between. The sun shone brightly through the glass panes, making the office feel slightly too warm for comfort.

One of the social workers left the room and returned a few seconds later carrying an old folder. He placed it gently on the large polished table in front of me. The folder had a strong musty smell and was yellowing with age and looked like it had been buried in some dusty filing cabinet for years until this moment. It was never meant to see the light of day.

I opened the folder with trembling hands and touched the untidy collection of papers inside. None of them were in any kind of order. They looked old and forgotten, destined never to belong to me. Yet they were all about me, the key which might unlock my early life and roots and answer the questions still haunting me even after so many years.

Picking up a page and reading it felt like biting on forbidden fruit. The two social workers sat quietly watching me and I sensed their discomfort. This was a new experience for us all. My mouth was dry and the only sound I heard was my heart pounding in my ears. Everything else in the room disappeared into the background.

Words like pneumonia, gastroenteritis, verminous, puny jumped out from the page, describing a child of 19 months I now felt no connection with. She was a stranger. The more senior of the two social workers broke the silence after spreading some of the papers on the table.

"Would you mind if I looked at this Patricia?", he said, holding up a crumpled piece of paper. "It's just that I've never seen something as old as this before."

I couldn't take in what I was reading. My eyes flitted from word to word, from top to middle to bottom of the page and then up again, in no logical order. I was trying to keep my emotions in check but the tears welling up inside made it hard to concentrate. No, I'm not going to cry in front of them, I said over and over to myself. Taking slow, deep breaths, I composed myself and lifted up my head slightly and looked at the social worker.

"No, go ahead, I don't mind", I said quietly.

I picked up an old school report filled with unflattering comments. Patricia is a dreamer...doesn't try hard enough...head in the clouds...Patricia's not very bright... The senior social worker asked if he could read it.

Then he looked at me sympathetically and said, "You know Patricia, most kids brought up in care never did very well."

"I suppose it's true. I certainly wasn't too bright."

Old memories flooded back. The never ending taunts of homey kid made me stand out from the other kids. I felt ashamed of who I was and where I lived. I didn't want to know much about school after that.

The file contained small memos, records of telephone conversations and messages passed between social workers. The words wanted by the police carelessly scribbled in pencil on one of them stood out. But I was no criminal. I was 15 at the time and deeply unhappy after years trapped in the care system. I wanted out. When the police caught me after four days on the run, I was returned to Aberdeen in handcuffs.

The senior social worker asked me if there was anything I wanted to talk about. He was being kind, doing his best to help me through a difficult afternoon. I told him no, there wasn't. How could I explain in a mere handful of words how I felt when I didn't really know myself? I wasn't ready to confront the pain and injustice of my long years of loneliness in the children's home. I didn't want to remember the teenage years which followed. They were hard miserable years and I paid dearly for all the mistakes I made. But I was lucky, even as I struggled to make sense of a world without family or friends around me for support. I survived, somehow.

The afternoon was a

ll but gone and many questions had been answered. But not all of them. I knew now I was ill in hospital with pneumonia and gastroenteritis and then taken into care as soon as I recovered. The Aberdeen authorities thought they were saving me from a life of poverty and squalor.

The papers were gathered up from the table and placed carefully back in the file. Soon, it would be returned once more to the dusty filing cabinet from where it came and forgotten about. It was time to leave.

"You proved them all wrong, no matter what they wrote about you", said the senior social worker, shaking my hand. "It would have been nice if the file had told you something about your roots."

He was right. His words kept spinning around in my mind as the lift descended to the ground floor. The doors opened and I stepped into a busy foyer bustling with activity. It was a relief to be back in the present. I left the building and stood in front of it for a few minutes, pondering on the events of the afternoon. I was lost in thought. People passed me by wondering what I was doing. The rush hour started but I hardly noticed. The file told part of the story of my earliest years but so many pieces of the jigsaw were still missing. I had to find out more.

By coincidence, I was just beginning to build up a long distance telephone relationship with my sister Mary Anne, who lived in a remote cottage in the Scottish Highlands with her husband. I remembered meeting her for the first time when I was four. No one told me who she was or that she was my sister. It wasn't considered important enough. When we met again in 1996, at my dad's funeral, more than 30 years had passed. We crossed paths for only the third time in our lives at my mum's funeral, a short while after. So we talked a lot on the telephone. We had so much to catch up on.

* * *

I was born in a former army barracks in 1955. That much I already knew from my birth certificate. Castlehill Barracks was the home of the Gordon Highlanders until they left in 1935. The barracks was taken over by Aberdeen Corporation and later used to house traveller families. I lived there for the first 19 months of my life and Mary Anne for 11 years.

Home for most of the year was two small adjoining damp rooms with bare walls and floorboards and a single gas lamp for lighting. Nine of us lived in the rooms including my mum and dad. There was no electricity or hot water to wash with or to keep clothes clean and only one double bed, which we children all slept in.

Jobs were scarce and my dad turned his hand to just about anything to earn a shilling or two. Sometimes he found work at sea on the trawlers or he and mum would go hawking around the doors, selling old clothes and anything else they picked up in the market in the Castlegate.

When spring arrived, we all piled on the back of a horse and cart and travelled the countryside for weeks on end. Sometimes we met up with other travellers, either on the road or at the traditional camping grounds, where we exchanged news and told stories and sung songs around the camp fire.

For many years, I was puzzled by a recurring vision which I could never explain. In the vision, I saw a young woman, standing tall and straight, her long black hair blowing in the wind. She stood silhouetted against the sky and the rolling hills in the distance. There was always a sense of happiness with her. I knew she loved the freedom and the emptiness all around her.

Then, quite by chance, a book I was reading had a photograph in it showing the traditional traveller camping ground at the Bay of Nigg, just outside Aberdeen. There was something familiar about the photograph which I couldn't put my finger on. I was certain I'd never been there before.

As I casually traced the outline of the distant hills with my finger tips, I suddenly realised they were the same as the hills in my vision.

Now I understood what I was seeing all those years. The vision was actually my earliest memory, a fragment of that summer in 1956 when it was still possible to experience the traveller way of life. The woman in the vision was my mum.

When the summer was over, we returned home because the law demanded all traveller children should attend school for 200 days out of every year. The miserable conditions at the barracks gradually grew worse over the winter months until they finally took their toll. The day I was taken into hospital was the last day we would ever spend together as a family. The Cruelty called shortly afterwards and took all my brothers and sisters into care.

* * *

Seven years later, as I walked through the Castlegate on the way to the Salvation Army's Citadel mission hall with my cousin Anne, I knew little about my family, or Castlehill Barracks, even although it lay only a short distance away. We were happy to escape the children's home for a couple of hours and sing for the down and outs who gathered at the Citadel every evening.

The air was filled with a strange odour, a mixture of decay, poverty and cheap wine, which I didn't recognise at the time. The down and outs were hungry and desperate and had no option but to endure endless prayers and our hymn singing if they wanted a hot bowl of soup and a bed for the night. In the morning, they'd be thrown out into the street again to face another hopeless day.

I didn't understand any of that at the time. All I saw was the old man with the matted yellow hair and weather beaten red cheeks sitting in the front row of the hall. Now and again, he looked up from the precious bowl of soup cradled in his dirty hands to the small stage where we stood, neatly dressed for the occasion. Each time our eyes met and locked for a brief second, a fleeting, nervous smile crossed his face. As the smile turned to a wide grin, a gaping chasm opened up revealing a mouth with not a single tooth in it. A second later, his head dropped down to the bowl and the loud slurping sound everyone was trying hard to ignore rose once more above the sound of singing.

It was all but impossible to praise The Lord in between the slurping noises and Anne warbling out of tune next to me. My feeble attempts at singing finally turned into fits of laughter. I couldn't take my eyes off the old man's face. It was now contorted and misshapen as he struggled to chew on a slice of hard crusty bread. I found it all so funny.

I couldn't help thinking about the old man on the way back to the children's home. There was something about his eyes which made me feel very sad. I didn't mean to laugh. It was just the reaction of innocence. Little did I know one day, in the not too distant future, I would be where he was now, walking the same path and feeling rejected and alone and struggling to survive in a heartless world.

Chapter Two

I fearlessly launched the little three wheeler bike down the small grassy mound, tightly gripping the handlebars. My long wavy hair lifted and billowed out in the air behind me. Ahead was a grand old white painted house. The scent of heavily ripe apples hung in the air. All around me was the sound of children laughing. But I barely registered them. I was happy to be in the warm sunshine in my own little world.

The bike came to a halt and I felt a sharp tug on my hair. I turned around to see a cheeky little black haired boy looking back at me. It was Alan.

"Go away!", I shouted out.

He didn't stop. Instead, he teased me all the more, pulling harder at my hair. It felt painful. I lost my temper and started to cry. Alan ran away.

It was now the middle of the afternoon. A lady was gently leading me by the hand down a winding path where rays of sunshine sparkled through tall bushy trees. As we walked, she sang Teddy Bears Picnic over and over and over. I wouldn't let her stop because I loved the song so much. It was my favourite.

I never knew the name of the lady who took my hand. I just liked her and loved to be in her company. She taught me to sing the song on our numerous little outings together. I was around three at the time or maybe slightly older. Whenever I heard it over the years, I immediately thought of her and those happy moments walking through the woods.

She was probably one of the nurses who worked in the white painted house, Pitfodels Residential Nursery in Aberdeen, where I was first taken into care after recovering in hospital. She wore a matching black trench coat and neat little hat which must have been part of the uniform. Not long afterwards, Pitfodels c

hanged and was renamed Airyhall Children’s Home. I never saw the lady again.

Even although I was always blessed with an excellent memory, only small snippets still stand out clearly. One in particular has never left me, yet it happened over 50 years ago. It was the day I met a sulky looking little boy with bright ginger hair. He was being dragged by the hand towards me while I was playing alone in the garden. I didn't pay too much attention at first.

No Easy Road

No Easy Road